An introduction to natural philosophy

Natural philosophy is considered a concept of the past. The term encompassed many variations, but according to Edward Grant in A History of Natural Philosophy, its earliest interpretation can be assigned to ‘all inquiries about the physical world’[1]. The word ‘“nature” coming from the Latin word natura, for which the Greek equivalent is physis.’[2]

The term natural philosophy and its discipline have evolved based on its interpretation of each culture and set of knowledge. Even though the term itself originated from the ancient Greeks, we can assume that the inquiry into nature comes with human existence, the wonder and curiosity humans must have from exploring their surroundings and looking up to the stars at night. This may not necessarily be a simple thirst for knowledge but as a means of survival and development.

Edward Grant traced the concept back to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia for their written records. ‘The surviving literature reveals a great emphasis on mythology and religion as the means of explaining the creation of the world and its operation. There is also a rather practical interest … in the area of astronomy, mathematics, and medicine.’[3] It was the Greeks who ‘eliminate the gods as the causes of natural phenomena and replace them, with natural causes’.[4] The ancient Greeks substituted supernatural explanations with logic and reason.

The discipline was thriving under Aristotle (384–322 BC), who set out to ‘define natural philosophy and delineate its scope, as well as to determine the best methodology for applying it to nature’[5], said Grant. He did not intervene with nature or experiment on it but observed it objectively and respectfully. Aristotle’s works in natural philosophy cover topics from biology to logic and the cosmos. This work, along with its commentaries, interpretation, and reevaluation written by his students and supporters, continued to influence the Western world up until the 16th century.

During the medieval period, natural philosophy was closely linked to theology with many religions using Aristotle’s work to support their religious beliefs. The work was translated from Greek to Latin, Greek to Syriac, and Syrian to Arabic.

It’s apparent that an inquiry into nature is not limited to any civilization or society, even if they may not share the same term. In China, Lao Tzu’sTaoism (6th – 5th BC) showed a way to understand and live in harmony with nature and the universe. Calendars from India have been found in Southeast Asia since the 7th century and could be used for agriculture and ceremonial purposes. It was not based merely on an observation. ‘(T)here are numerous examples of correct planetary positions … which were patently not observable. The calculations that produced a calendar were (and are) enormously complex. These included very sophisticated mathematical operations’[6], wrote David K. Wyatt.

However, it was the change that started in 17th-century Europe that transformed natural philosophy into science as we know it today. The invention of instruments such as telescopes, microscopes, and barometers revealed things that could not have been perceived earlier.[7] This led to discoveries that challenged the old beliefs linked to the Aristotelian natural philosophy.

Another crucial shift was how natural philosophers in that period not only observed but also experimented on nature. The founding of the Royal Society, which included members such as Francis Bacon (1561–1626), Robert Boyle (1627-1691), and Isaac Newton (1642-1727), encouraged the exchange of knowledge, promoted the experimentation method, and urged science inquiries to be separated from theology.

In his book, Edward Grant wrote about this crucial time, ‘By the end of the seventeenth century the transformation of natural philosophy was manifested in Isaac Newton’s Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy’.[8] He continues, ‘By extending the application of the term natural philosophy to the mathematical sciences, most notably mathematical physics, Newton may have begun a tradition that reached fruition in the nineteenth century when natural philosophy came to be called physics, and, often enough science in general’[9].

The term natural philosophy has been transformed into natural science and then to just science (‘The word ‘science’ comes from the Latin scientia, which means ‘knowledge’’[10]). Still, ‘throughout the nineteenth century the terms natural philosophy, physics and science were used synonymously’[11]. However, once science became focused on a more specific branch with its own theory, methodology, and discipline, the term natural philosophy became obsolete.

Natural philosophy in the 21st century

This project was initiated from a love of art and science and a fascination with the story of the search for knowledge throughout human history. What is interesting about the concept of natural philosophy lies in its interdisciplinary nature, combining various fields concerning the world around us.

At one point in history, natural philosophy could encompass physics, biology, chemistry, medicine, astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, theology, and even alchemy. It aimed to explore and explain the whole scope of the natural and physical world and humanity’s place within it. Each natural philosopher studied and could be interested in various topics simultaneously, as everything seemed interrelated and connected.

The openness to inquire across broad subjects was stimulating and refreshing, compared to the present, where most research and study involve an in-depth focus on a specific topic. Undeniably, this is due to the necessity and practicality of considering the magnitude of data and information that have to be processed and procedures that must be conducted proficiently.

Working in the art sector, I have seen many artists pursue artistic projects that involved various fields or were cross-disciplinary. Consequently, I started to form the notion that it could be said that in current society, the spirit of natural philosophy may be found in artists and their practice. Artists have the freedom to pursue any topic of interest. There is no limitation in terms of their chosen subjects or working processes. They can look into anything that fascinates or affects them directly or indirectly. But instead of inquiring through a scientific method, they do it via the artistic process and represent the result as works of art.

The concept of linking artists to natural philosophy is not new. In The Body of the Artisan, Pamela H. Smith wrote, ‘Until recently the story of the Scientific Revolution was largely told as a narrative about theoretical change: … it leaves out the large numbers of individuals who began to show interest in and to practice the “new philosophy” but who did not contribute directly or explicitly to theoretical change.’[12]

In the same book, she wrote about Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), a German painter and printmaker. ‘The certain knowledge residing in nature – there to be extracted by the artist – could not be divorced from matter itself. For Dürer, art rested on a knowledge of the variety and particularity of matter and nature.’[13] She adds, ‘They (the artisans) articulated ideas about the pursuit of natural knowledge-an epistemology-as well as theories about the operations of nature and of their own imitation of nature by art more fully, and in written form’.[14]

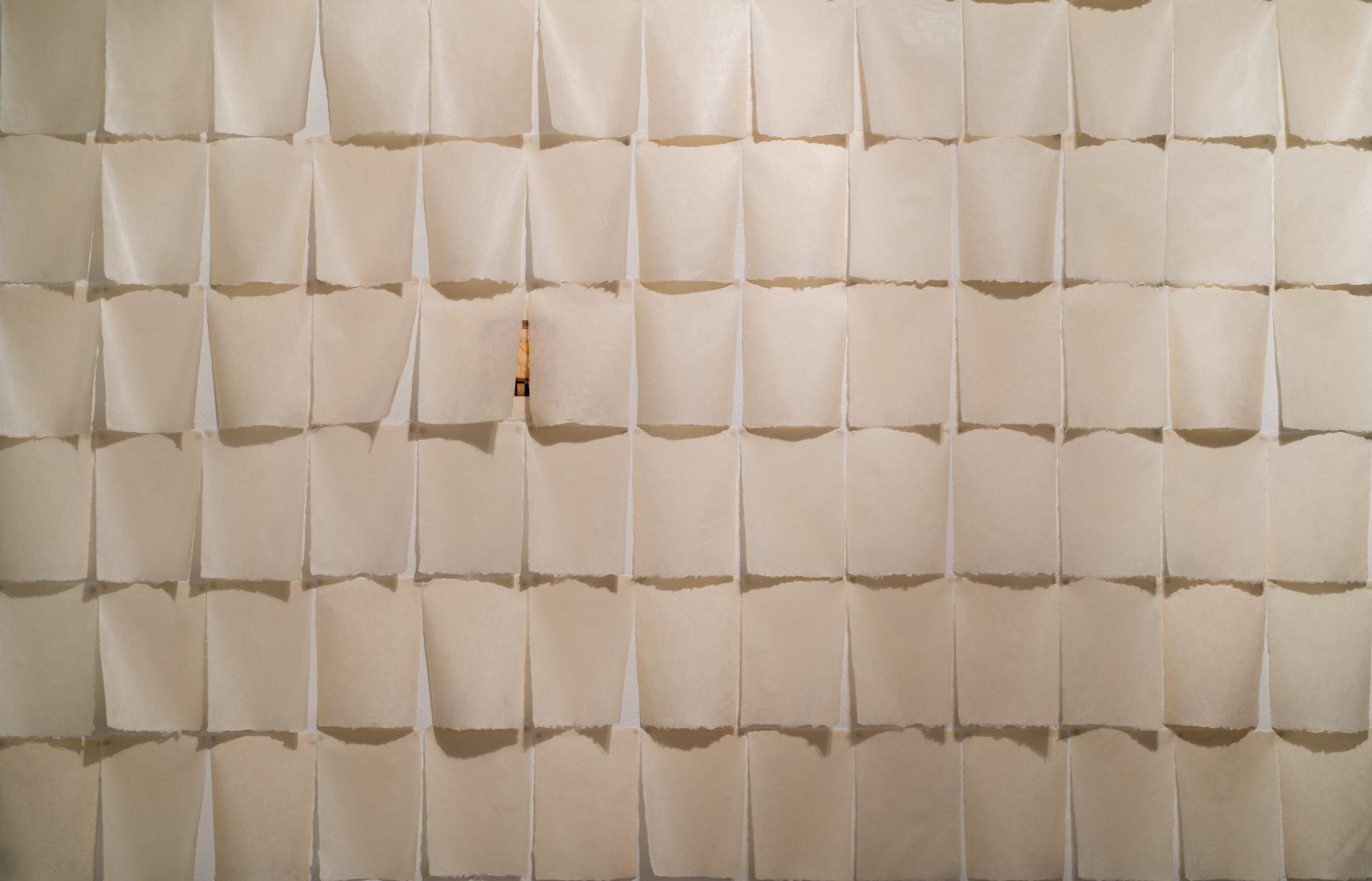

In this exhibition, a group of artists represent the reconstructed concept of natural philosophy. Unlike natural philosophers of past centuries, these artists reflect not only on the natural world but all the physical world with its social and political structure within it. Each artist starts with his own set of questions and investigations. Their quest leads them to various subject matters.

Naraphat Sakarthornsap documented bougainvillea for his new series Bract and Flowerpot (2024). Bougainvillea is a native plant of South America, but it has become popular due to its multiple colors and durability, and it can now be found everywhere in Thailand. People tend to misunderstand its colorful bracts for its petals. Sakarthornsap surveyed and photographed the flowers across many locations in Bangkok.

This record was done with keen attention to the details of the surroundings, including man-made structures and the plots or pots they had been planted in. For Sakarthornsap, each bougainvillea in various settings could be used to reflect the social structure of the city. Its environment signifies its boundaries and limitations. Observing its condition could reveal the grower’s intention and attention toward the plants.

Ruangsak Anuwatwimon presents his ongoing series, Anthropocene (2008 – present). His practice usually involves research into the consequences of human activities and progress toward an environment, nature, fauna, and flora. He often collaborates with scientists and experts specializing in certain topics. He frequently collects samples from natural environments and areas of interest as a testimonial of human action.

In Anthropocene, he reconstructed a new landscape from toxic soil collected from various parts of Thailand. The work represents a contemporary landscape filled with waste from human consumption where our behavior and actions have damaged an ecosystem. It acts as proof of the failure and possibly illegal methods in waste management and law enforcement.

Involving the notion of landscape, Jinjoon Lee presents two series of works. Manufactured Nature: Irworobongdo (2022) is inspired by the landscape paintings on Irworobongda (Korean folding screens). Using deep learning and collected datasets results in a fabricated spatial narration that represents the transient stage of natural occurrence. The intentionally green hue chosen to signify nature is in stark contrast to the new technology used. This challenges a viewer’s perception and interpretation of reality.

Another work is On Air Garden (2024), the artist’s latest development. It is a video installation created in response to a brainwave, with a virtual scape created from a set of images from news and occurrences during a two-day period from 31 December 2023 to 1 January 2024. The work aims to reflect on our media consumption and perception through mass media, which seems to detach us from the suffering, distress, and disasters happening in reality.

Phornphop Sittiruk examines human evolution. He is fascinated by our ability to think, explore, develop, and solve problems. He sees how the progress of human civilization tends to create problems attached to it. Humans then come up with a solution and action, which, in turn, leads to another issue. He is trying to find an answer to this dilemma and asks: why do humans continue to evolve in this cycle?

His research looks back to early human society and evolution, and he presents his findings through multiple art objects. Each piece, with its visual and material symbolizations, represents crucial events in human history. His interest is in science, not hard science, but in social sciences as a way to understand human behavior, decision, and action.

All these artists have acquired working processes and outlooks that could align with natural philosophy concepts and methodologies. They exercise multiple approaches and practices in combination with the artistic process.

Sakarthornsap searches for an understanding of the social inequality in the city he lives in. This is done through an observation of the bougainvillea which is a contribution of humans living in the city from each community. He hopes to uncover the insights that will help him interpret the city’s social scape. Anuwatwimon not only researched through multiple news and information sources for an area with toxic waste problems, but he went to the site to collect the samples. He then took it back to be scientifically tested to find their components and chemical contamination which will act as evidence of the toxic waste found in a populated area.

Lee’s interests are in human psychology, perception, consciousness, and sensory experience. He considers his work to entwine ‘anthropological research’ with ‘personal introspection’. Using technology to create constructed spatial and temporal conditions would reveal insight into the human mind. Sittiruk pays attention to his choice of material based on its natural aspects. Not only has he created art objects from organic and non-organic materials, but he has also experimented using information he gained through his study and grew potatoes to understand the food source. This eventually became part of the work in this project.

Being able to collaborate and work across multiple disciplines allows these artists to dive into their inquiries through artistic operations. With a broad outlook, they present their work as a whole picture, linking relevant areas of study. What is truly striking and unique is how they present the acquired knowledge through artistic process and production.

It is the nature of a work of art to be open for interpretation, which can result in something beyond the producer’s imagination and expectation. This way of interpretation seems relevant and suitable for this complex and manifold contemporary society, where it appears that the control of people’s narratives and thoughts results in stagnation and recession. The artwork, along with its findings and examination, can lead to an accumulation of knowledge added to by viewers who bring their own perspectives and interpretations, creating a dialogue that increases the scope of inquiries.

Prior to this project, I was unaware that the idea of revisiting natural philosophy had been discussed in the fields of philosophy, history, and social science for some time. Scholars have written many texts relating to these topics.[15] Some see the advantage of the interdisciplinary approach, and many seem to focus on its virtues and moral aspects.

This is not surprising considering the state of our world today, with critical environmental issues, conflicts and crises in our society. Unlike what was suggested by some of these authors, the initial intention of this exhibition was not about the ethical standpoint of the lost discipline but on knowledge acquisition and understanding. Nevertheless, I hope that by seeing the grand scale of an issue, with its cause and effects, through the well-thought-out artistic and research process, good judgment, outlook, and action will automatically follow from both the artists and the audiences.

Nim Niyomsin, Curator

[1] Edward Grant, A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (USA: Cambridge University Press, 2007). P. 1

[2] David Wootton, The Invention of Science: A New History of the Scientific Revolution (UK: Penguin Books, 2016), p.25

[3] Edward Grant, A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (USA: Cambridge University Press, 2007). P. 1-2

[4] Edward Grant, A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (USA: Cambridge University Press, 2007). P. 8

[5] Edward Grant, A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (USA: Cambridge University Press, 2007). P. 42

[6] David K. Wyatt, Siam in Mind (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2002), p. 43-44

[7] Through the telescope, Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) discovered the moons of the Jupiter and the Sunspots. His finding helped confirm the heliocentric model that the Earth and other planets rotates around the Sun.

[8] Edward Grant, A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (USA: Cambridge University Press, 2007). P. 307

[9] Edward Grant, A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (USA: Cambridge University Press, 2007). P. 316

[10] David Wootton, The Invention of Science: A New History of the Scientific Revolution (UK: Penguin Books, 2016), p.23

[11] Edward Grant, A History of Natural Philosophy: From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (USA: Cambridge University Press, 2007). P. 318

[12] Pamela H. Smith, The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), p. 18

[13] Pamela H. Smith, The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), p. 74

[14] Pamela H. Smith, The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), p. 59

[15] Examples are Nicholas Maxwell, In Praise of Natural Philosophy: A Revolution for Thought and Life, and Alister E. McGrath, Natural Philosophy: On Retrieving a Lost Disciplinary Imaginary